Local Deployment and a Glimpse Into Trek's CI/CD System

One of our goals as the Trekkers was always to be able to have a cost-effective but performant deployment of Trek. As someone who self-hosts their own server for their personal site, I thought it would be quite suiting to see if our current needs for deployment and CI/CD could be met through repurposing part of self-hosted solution.

My Site

As a little bit of background, my personal site (https://wyfx.ca) was originally started as just a way for me to take the Raspberry Pi I had sitting at home and make it something useful.

The site was developed under Vite, and deployed under a Docker container running nginx. Whenever I have a new version of the site, I build a new version of the Docker container, then manually restart the container.

At Trek, one of our priorities is always knowing about the status of our product. Hence, with some of my knowledge on the team, we aimed to leverage that knowledge to develop our own self-hosted solution for development purposes.

Considerations

On the implementation side, moving from a simple statically hosted website to an integrated solution with our GitHub workflow would not be easy. Our goals for Trek's deployment solution would be something that is integrated with GitHub, performant enough to run on my Raspberry Pi, and automatic. This solution would be key for our CI/CD process and would ensure that we'd able to quickly iterate on new updates to our codebase.

Security

Security was especially important to me as we needed a solution that would not expose my self-hosted server to too much risk, but would still be able to automatically integrate with GitHub. My home server did not have a publicly exposed SSH port, yet without one we would not be able to upload files to the server. However, as my main account on the server was an administrator, I did not want any possible SSH solutions to have full access to the administrator account.

Performance

The second primary consideration with our design was performance. This includes both the "visible" parts of the site (like API and frontend), but also the build process from a successful push to GitHub. While we would not have to worry about a large amount of users on the development site, we still wanted a solution that would be performant enough for us to evaluate how the site would behave for production deployment in the future. The limited compute power of the Raspberry Pi also means that this deployment needs to be as lean as possible.

Maintainability

The last key consideration was maintainability. The development of Trek moves quickly, so our system should be able to adapt to those changes quickly. Without a maintainable system, the system could quickly become obsolete - sacrificing valuable developer time.

With all of our considerations in mind, we started the design of the CI/CD system.

Deployment

Since I was most familiar with a Docker container setup like my home server, my

initial thoughts were to create another container running on the server at the

same time as my personal site. So the first challenge was coming up with a

deployment that would allow both Docker containers to run at the same time while redirecting

to different domains.

My solution to this issue was to use

nginx-proxy. nginx-proxy

essentially acts as a reverse proxy that routes to Docker containers by

subdomain. Now, I can start my own website's container with an environment

variable VIRTUAL_HOST=wyfx.ca, while having Trek on a subdomain like

SUBDOMAIN.wyfx.ca. To handle HTTPS, I extended my original LetsEncrypt

certificates using

acme-companion, which will

automatically generate a new HTTPS certificate for each of my subdomains by

specifying LETSENCRYPT_HOST=SUBDOMAIN.wyfx.ca.

The largest decision to make was how to get updates from our GitHub repository. As I didn't want to expose a public SSH port on my home server, I initially thought about a solution that wouldn't directly connect the GitHub repository to the server. Instead, the server could poll for changes on GitHub, and when changes are detected, the following would occur:

- Pull the changes from GitHub

- Build a new container

- Restart the running container

However, we did not end up going with this idea for a few reasons:

- Unless we polled at a very fast rate, there was still going to be a delay before we could even detect a change from GitHub

- There were concerns with performance from the fact that the Raspberry Pi would have to do all the building

- We would have to create our own scripts to make the polling + building possible, which would each cost us maintenance time

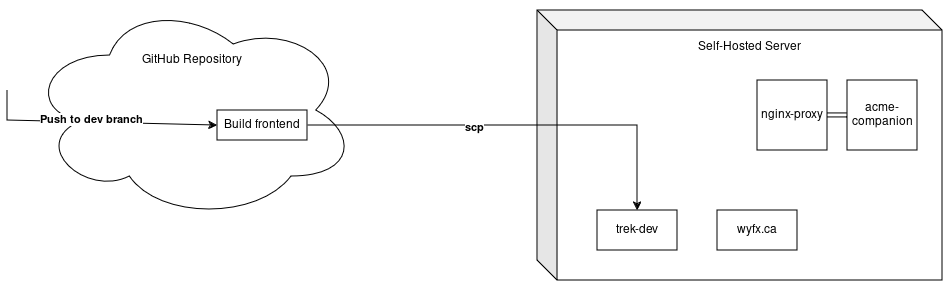

The solution we ended up using for the frontend was to create a nginx Docker container that is also running a SSH server. Then, to update the frontend, we could write a GitHub Action to build the frontend, then SSH into the Docker container and replace the static files in the container. This solution was much simpler, which would make it easier to maintain. It also does not involve constantly rebuilding the Docker container, as we would be making local updates to its filesystem instead. In addition, having the publicly exposed SSH port be into a container would gave me some more comfort that any attacks would not be able to immediately access my entire server (though such attacks are possible).

Our GitHub action to build and upload the frontend is included in the

Appendix. It builds our frontend using npm, and then

uploads it via SCP to the Docker container using

appleboy/scp-action. This ended up

looking like the following:

name: Deploy Frontend Dev

on:

push:

branches:

- "project_[0-9]-dev"

jobs:

deploy:

name: Deploy FE Dev

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

concurrency: deploy-group # optional: ensure only one action runs at a time

steps:

- name: Checkout

uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Build FE

run: |

cd frontend

npm install

npm run build

- name: Upload to server

uses: appleboy/scp-action@v0.1.7

with:

host: REDACTED

username: REDACTED

password: REDACTED

port: REDACTED

source: "frontend/dist/*"

target: REDACTED

overwrite: true

strip_components: 2

For the backend deployment, we built off of the frontend deployment. Our backend

deployment uses tsc-watch to start up

our backend server, and then monitor for file changes. Then, a GitHub action is

triggered whenever a push has been made to our dev branches, uploading the files

via SCP. tsc-watch is built to automatically detect those changes and rebuild

the backend dynamically as its files change. To support the communication

between our frontend and backend, the backend runs under the same nginx server

as the frontend. Requests to our API endpoints (e.g. /api/v1/users) would then

be forwarded to the backend server, allowing us to remain under the same

subdomain and avoid spawning too many Docker containers for the server to

handle. To make this happen, our nginx.conf includes the following:

server {

location /socket.io {

proxy_set_header Host $host;

proxy_set_header X-Real-IP $remote_addr;

proxy_pass REDACTED;

}

location / {

root REDACTED;

index index.html;

try_files $uri $uri/ /index.html;

}

location /api {

proxy_set_header Host $host;

proxy_set_header X-Real-IP $remote_addr;

proxy_pass REDACTED;

}

error_page 500 502 503 504 /50x.html;

location = /50x.html {

root /usr/share/nginx/html;

}

}

By overwriting what happens with the location /api line configuration, we are

able to redirect requests to go to the backend server rather than still going to

the frontend.

The Future

As Trek continues to develop, our CI/CD system will have to evolve too. One of our upcoming goals for a future sprint is to integrate testing frameworks into both our frontend and backend. When our backend develops more, we might also find that the self-hosted server won't be powerful enough. However, with our maintainable and reproducible system, we are well-equipped to handle these future challenges with ease.